Terrence Guyula - Aboriginal Health in Aboriginal Hands

Terrence Guyula is an Aboriginal Health Practitioner who has worked in the remote Top End of the Northern Territory for over 32 years. In 2016, we highlighted Terrence’s experience with secondary prophylaxis delivery. We recently caught up with him again to talk about his unique style of breaking down complex health information for Aboriginal people with ARF and RHD, and translating the needs of the Aboriginal community for the wider health workforce.

Terrence is a clinician, community Elder and advocate for men’s health. He is a senior Aboriginal Health Practitioner who, for more than 30 years, has worked on several public health programs through the NT Disease Control - Public Health Unit including tuberculosis, leprosy, sexual health and rheumatic heart disease (RHD).

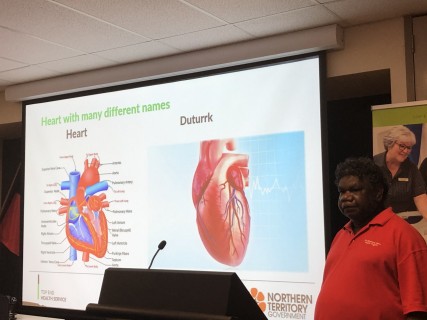

Earlier this year, Terrence joined staff from the NT RHD control program to deliver a series of workshops at the Royal Darwin Hospital, Danila Dilba Health Service, and the Batchelor Institute.

Earlier this year, Terrence joined staff from the NT RHD control program to deliver a series of workshops at the Royal Darwin Hospital, Danila Dilba Health Service, and the Batchelor Institute.

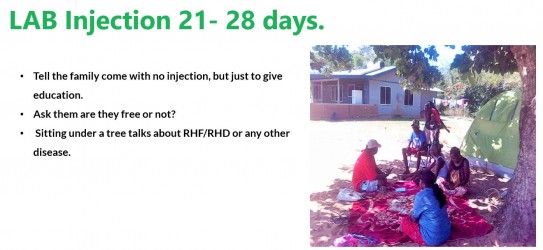

One of his presentation slides included an image of a group of people sitting under a large tree having a conversation. He pointed to himself in that photo and said that he was having a talk with a family about RHD. He spoke about the importance of building a relationship with the family and communicating with a man who wanted for more information for his grandchild who had RHD.

“The only way to do that is for me to go there all the time so they know - talk about my family, talk about my line connection because from the north from Gove, Angurugu, Umbakumba, Galiwinku and Gapukwiyak, Barunga, Ngukurr, Nhumbulwar, Groote Eylandt, Ramingining, and Millingimbi; there is a connection line there, family relations and that is very important, so they know who I am.

"I just want to give a clear picture and a clear story. That’s how I want to do when I do my education back home. If you look at the photo of me sitting under the tree, the grandfather doesn’t know about 21-28 days (penicillin injection frequency), he only knows about 28 days.

"So, I tell him it’s due from 21 days to 28 days. The grandfather was really interested and asked me a lot of questions. That makes me happy and it feels like I gave the right story. When we talk to the people and see the people happy and smiling we know that we gave the right message”, said Terrence.

"So, I tell him it’s due from 21 days to 28 days. The grandfather was really interested and asked me a lot of questions. That makes me happy and it feels like I gave the right story. When we talk to the people and see the people happy and smiling we know that we gave the right message”, said Terrence.

When asked about his presentation to Royal Darwin Hospital staff, Terrence said, “This is the first time I’ve made up my own presentation. I did a lot of thinking. How do I do my presentation? Make sure the staff don’t go to sleep, or get bored. I want to make them happy, laugh and funny way but at the same time take serious. My life born in that you know, I want to make happy people.”

| Terrence was presented with his Aboriginal Health Worker Certificate by Prince Charles and Princess Diana in Darwin on 2 February 1988. |

Even though he’s been working in the Top End a long time, Terrence is still trying to find new ways to bring ARF and RHD education and awareness to the people of the Northern Territory, including to other health professionals, who he believes can learn valuable lessons about working cross culturally.

Desley Williams from the NT RHD Control Program says that health staff have a lot to learn from Terrence.

“Firstly, don’t underestimate his knowledge, skills and experience, because he has much to offer. He is a particularly good educator and knows just how to provide information, particularly to the people of East Arnhem, in a way which is meaningful to them. He is also able to share this skill with Aboriginal staff from other regions, and that prompts them to consider how they can adapt his approach when providing information to their communities.

"His ability to listen and absorb information has led to him becoming a very knowledgeable and respected practitioner. He often sits quietly but all the time he’s listening. He’s a great storyteller, and new staff really appreciate the opportunity to be educated as well as amused by these stories,” said Desley.

Terrence has worked in Gunbuylana (Oenpelli), Gapuwiyak (Lake Evella), Yirrkala, and Nhulunbuy (Gove), and has long cared for people living with ARF and RHD. He provides direct clinical care including administering regular penicillin injections, and says he is motivated to end this disease for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

“All I want to do is try and reduce new cases of rheumatic heart. It’s hard, but you need to keep trying, you know. It’s like my home you know, when someone tries to tell me where to get another job, I can’t, it’s like my home.”

In 2020, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reported that most ARF diagnoses (95%) were among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and the 2016 population census shows that in the very remote communities of Australia such as where Terrence works, less than 33% of the population speaks English at home.

There’s a lot of complicated messaging that needs to be conveyed, and with that, the probability for misunderstandings and missed understandings increases. With the high burden of ARF and RHD in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and a health system designed around the English language and medical-model culture, there are bound to be gaps in communication; therefore, the role of people like Terrence who can explain things in language and in a way that crosses complex cultural understandings and ways of thinking has never been more important.

Terrence, through his many years of experience and natural teaching ability, can bridge the gap between western and Aboriginal language and culture. This makes people feel more at ease and in turn gives them the confidence to know what they need to do to take care of themselves.

But it’s not just about being able to speak to people in their own language; it’s also about being able to walk in two worlds and make sense of western medicine through the lens of Aboriginal culture. That’s where Terrence, through his expertise in medicine and his understandings of Aboriginal culture, can help people understand the medical information doctors are presenting to them.

But it’s not just about being able to speak to people in their own language; it’s also about being able to walk in two worlds and make sense of western medicine through the lens of Aboriginal culture. That’s where Terrence, through his expertise in medicine and his understandings of Aboriginal culture, can help people understand the medical information doctors are presenting to them.

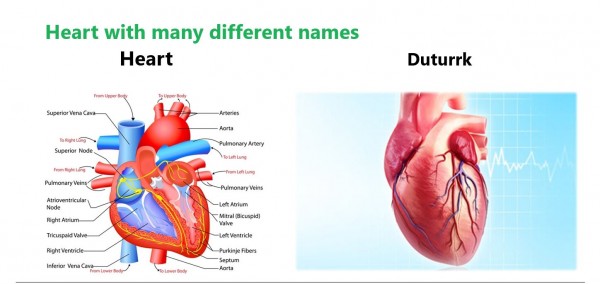

“It is really, really important for the people that need to know [about ARF and RHD], especially with the Aboriginal people. With the heart with a lot names is the Balanda way [western understanding], not the Aboriginal way. The heart I put on the right side is the Yolgnu way of understanding, this is how they look; with no names in English, but in Yolgnu there only a few words, not many of them.

"But people like me, the Aboriginal Health Practitioner, once we start talking about the parts, we are able to speak clearly on that even though we don’t have much names for the parts, but I’m confident I can talk about it exactly. But not out of what the doctor has to say about it.

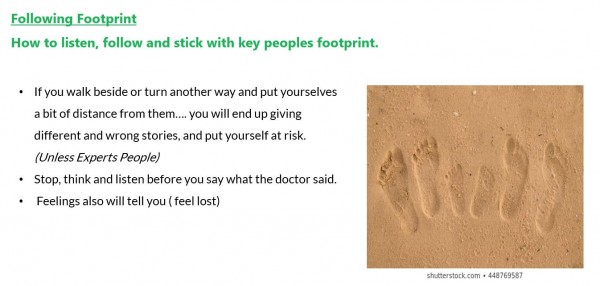

"I have to stay on the foot track as I was telling about the footprint in the presentation. That’s the meaning, the expert people, the Aboriginal Health Practitioner, we’re the only one who can talk about it – go around, going the other way around, sideways, across, and we want to let the doctor walk in the middle. And at the end, we make sure, where we meet up, we have the full information, clearly for Aboriginal people to understand. The footprints on the side are Yolgnu and the doctor in the middle. Even I go in a different direction, I still need to stick on what the doctor talks about. That’s the main thing. I just want to give a clear story, that’s how I do my education back home,” said Terrence.

"I have to stay on the foot track as I was telling about the footprint in the presentation. That’s the meaning, the expert people, the Aboriginal Health Practitioner, we’re the only one who can talk about it – go around, going the other way around, sideways, across, and we want to let the doctor walk in the middle. And at the end, we make sure, where we meet up, we have the full information, clearly for Aboriginal people to understand. The footprints on the side are Yolgnu and the doctor in the middle. Even I go in a different direction, I still need to stick on what the doctor talks about. That’s the main thing. I just want to give a clear story, that’s how I do my education back home,” said Terrence.

Terence’s dedication to helping improve the health and wellbeing of people and communities across the Top End has earned him renown and deep respect from his colleagues, and from the people in the communities he serves.

When asked about Terrence’s strengths, many of his colleagues highlight his strong connection to country, culture and community. Others speak of his warm nature, and his innate ability to teach and communicate with people from all walks of life. He has all the characteristics you would expect in someone who works to help people understand how to lead healthier lives.

Joy Pascall, who has known Terrence for 15 years and worked with him for the last 7 years, has seen him in action and knows firsthand how he connects with people and supports them to improve their health.

“Terence is a born educator,” said Joy. “He loves teaching the younger generation about how to keep themselves healthy and happy. He is a respected elder in our region and the younger generation always look up to him. He has a mighty passion for health and sharing his story for the Yolngu he also is a great leader and well-respected storyteller.

"He teaches us all something new every day, his stories are the best. He has some great memories of hunting and crocodiles. He tells a story with great enthusiasm and pride, you can see him reliving the moment. I think we can all learn something from him, especially when you hear his story and the Yolngu story of RHD is in his language,” said Joy.

Role of the Aboriginal Health Worker and Aboriginal Health Practitioner

There is considerable evidence that Aboriginal Health Workers and Aboriginal Health Practitioners are well-placed to deliver effective, culturally appropriate care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The 2019 National Aboriginal And Torres Strait Islander Health Worker Association’s position statement states:

"The unmatched roles of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Health Workers and Health Practitioners (A&TSI Health Workers and Health Practitioners) are pivotal to the delivery of culturally safe, responsive and effective health services across the Australian health care system. Greater valuing of and strategic investment in this uniquely positioned workforce is fundamental to achieving health equity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people."

Aboriginal Health Practitioners like Terrence play a central role in providing wholistic, community-based care and self-management support. They have an intimate understanding of community expectations, cultural priorities, and language, and can help translate the needs of the community to the wider health workforce.

Acknowledgements

We thank Terrence for taking the time to share his story and photos. Thanks also to Joy Pascall, Desley Williams and Hilary Bloomfield in Darwin for sharing their experiences of working with Terrence.

To learn more about culture and care, download the podcast series ‘Ask a Specialist’. Doctors from the Royal Darwin Hospital talk to Larrakia, Tiwi and Yolngu leaders about a range of clinical and philosophical issues that impact Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory.