Tackling the root cause of RHD

If Australia wants to get serious about tackling the root causes of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease, there are lessons to be learned from New Zealand.

That’s the message from Darwin-based Aboriginal Health Practitioner Maida Stewart, who was in New Zealand as part of her Winston Churchill Trust Fellowship.

Maida Stewart has worked as an Aboriginal Health Practitioner at Danila Dilba Health Service in Darwin, Northern Territory since 2003. She has seen hundreds of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with ARF and RHD, many of whom experience homelessness or live in crowded dwellings.

Maida wanted to learn more about what could be done to resolve the housing crisis found in many urban and remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, which is at the heart of Australia’s high rates of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and rheumatic heart disease (RHD).

Maida's Churchill Fellowship took her to Auckland, on Aotearoa’s (New Zealand) North Island, in early 2020 to investigate the Healthy Homes Initiative. It's one of several strategies to reduce the rates of ARF among Māori and Pacific Islander communities by addressing quality of housing and household crowding.

“There’s been a really strong focus (in Australia) on primary and secondary prevention to stop ARF and RHD, and as clinicians, we feel like we have a greater degree of control over these things. But when it comes to primordial prevention, which looks at things such as housing and environmental health, it feels beyond our control.

“I wanted to look at the big picture; to look at housing and health and the social conditions of poverty that, honestly, we put to the side because we don’t feel like we can do anything about it. I felt it was time to start looking into whether it was really true, that is, are we really powerless to change things at that level?” said Maida.

Maida examined Aotearoa’s Healthy Homes Initiatives to see what was working, what challenges were faced in implementing the initiative, and how innovation was used to develop Whānau (family) and Iwi (community) led solutions. She looked at new policies addressing health-related housing issues, and whether there had been any cost savings to the New Zealand government since these initiatives were first implemented.

“I spent the first two weeks in south Auckland, where there's pockets of low socioeconomic communities. There, I got to meet people from several agencies and organisations, including central and local government agencies, non-government organisations, public health, and philanthropic organisations.

“There are many challenges facing families in south Auckland, with many working poor and working homeless. You’ll find people working low paying jobs during the day and sleeping in their cars at night.

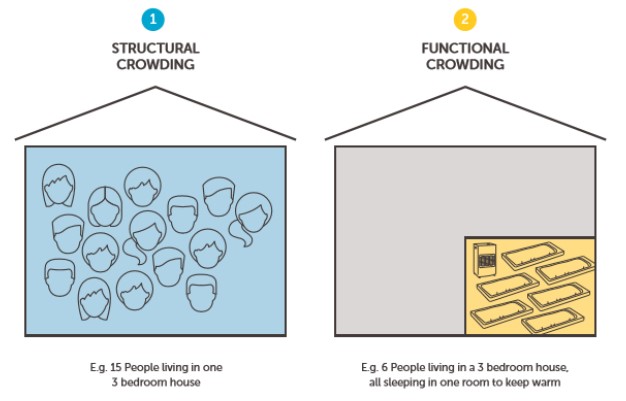

“Historically, low wages coupled with the high cost of living, poor quality housing, and poor housing regulation means multiple family members crowd into houses to fight the cold and damp conditions found in many homes, and to share the high cost of rent, food, and electricity. This results in the Māori and Pacific Islander communities living here to have very high rates of ARF.

“To tackle the issue of housing quality, the Healthy Homes Initiative employs what is known as a human-centred co-design approach. This means solutions to problems come from the lived experiences and insights of the Māori and Pacific Islander communities themselves,” says Maida.

“This encourages people living with the problem to come up with solutions with a learning-by-doing approach that uses prototypes and testing of ideas that leads to refinement. They take an idea and develop a prototype, test it, and if it doesn’t work, they scrap it and then try something else.

“They found that this generated solutions quickly and built the capacity and knowledge of communities. This methodology encouraged innovation and assisted in the development of practical housing and environmental health-related interventions that were ‘low cost, high impact, fit-for-purpose and locally relevant.”

The Healthy Homes Initiatives in Aotearoa provides cost savings to the health care system in the form of reduced hospital admissions and GP visits, and fewer prescriptions being dispensed. While some initiatives such as increasing the supply of affordable housing are challenging, other types of housing interventions can be implemented sooner.

The Healthy Homes Initiative explored the question “what can be done right now to improve the health of our homes”?

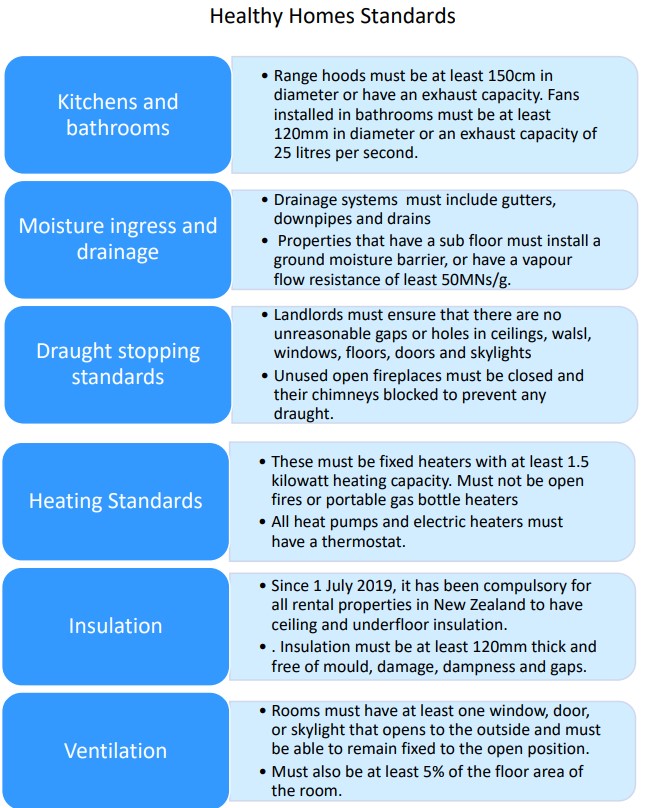

This led to solutions for interventions that were practical, readily available and affordable, making them accessible for families. Interventions such as implementing a minor repair service through Habitat for Humanity was low cost and high impact. Draft stoppers around doors and windows cost NZ$20-30. Bubble wrap on windows and double-lined curtains kept houses warmer and were easy solutions for keeping the heat in.

Improving the quality of current housing stock through refurbishments has also provided an interim measure to address overcrowding and improve living conditions while work is being done to increase housing supply across Aotearoa.

ARF is often referred to as a ‘disease of poverty’, because it is usually only seen in developing nations and low socio-economic groups in developed countries around the world. Environmental factors such as overcrowding and other housing related living conditions are associated with the exposure and transmission of group A streptococcal infections that causes ARF.

Australia’s Northern Territory has one of the highest rates of ARF in the world, and rates continue to increase.

“I absolutely believe there are things that we can do right now in Australia. If we look to Aotearoa and how they focus on human-centred co-design, we can, and should have similar initiatives to find solutions to the housing problems in both rural and remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

“But what we really need is a coordinated response from the Australian Government to address key housing and environmental health issues affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities with high rates of ARF and RHD,” said Maida.

There has been a growing movement for more investment from the Commonwealth to tackle the root causes of ARF and RHD in Australia. In September 2020, the RHD Endgame Strategy – a blueprint for eliminating rheumatic heart disease by 2031, was released. It calls on the Commonwealth Government to invest in five priority action areas, including a ‘Healthy Environments’ initiative that focuses on tackling the primordial causes of RHD by guaranteeing all communities have healthy housing and environments.